Yet the sense of place in Jazz, as Eudora Welty defines it in her essay "The Eye of the Story,"1 is a fledgling, tentative one which only timidly heralds Paradise's discrimination-safe haven. "Black Manhattan," as James Weldon Johnson used to call it, shapes up as a space of resistance in which all sorts of cultural practices resurface under oppressive conditions. The metropolis in 1926 is a vast receptacle of actual, historical, vocal, and memorial traces. It seems to be doing much more than encoding AfroAmerican place.

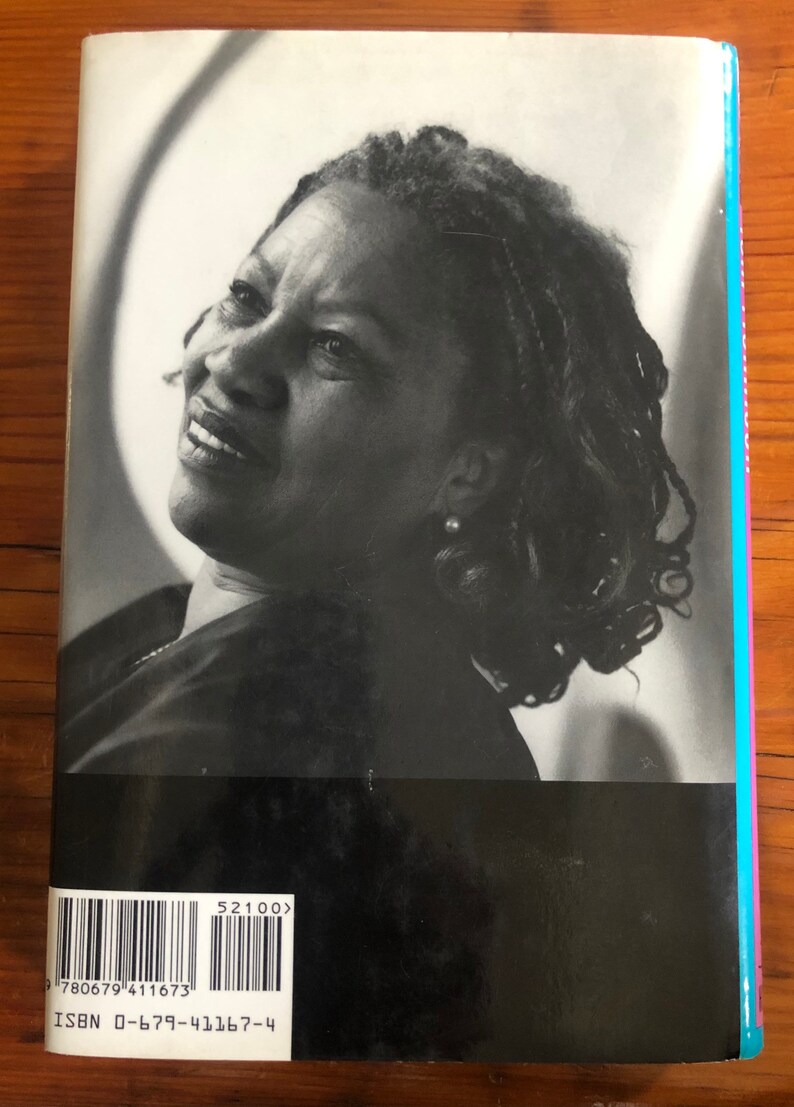

But what it consistently calls "the City" with a capital C only indirectly functions as historical background. The narrative's deliberately engendered, unspecific voice and its avatars take center stage against a Harlem backdrop. Out of the three volumes of Toni Morrison's trilogy starting with Beloved (1987) and ending with Paradise (1997), Jazz (1992) may very well be the most vocal.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)